China-Burma-India theater: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Jensen (add Hump) |

imported>Richard Jensen (add details) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==Strategy== | ==Strategy== | ||

see [[Joseph Warren Stilwell]] | see [[Joseph Warren Stilwell]] | ||

The stunning speed of the Japanese conquests in 1941-42 stunned China. In eight weeks the Japanese sank the American battle fleet at Pearl Harbor, knocked out American air power in the Philippines, captured Hong Kong, sank the British and Dutch fleets, captured Malaya and the impregnable fortress of Singapore, and finally captured Rangoon, cutting off the Burma Road lifeline to China. The British, primarily concerned with India, looked to Burma as the main theater of action against Japan and wanted Chinese troops to fight there. The United States conjured up visions of millions of Chinese soldiers who would hold the Japanese then throw them back, while providing close-in airbases for a systematic firebombing of Japanese cities. Chiang realized it was all fantasy. On the other hand there were vast sums of American dollars available if he collaborated. He did so and managed to feed his starving soldiers, but they were so poorly equipped and led that offensive operations against the Japanese in China were impossible. However, Chiang did release two Chinese armies for action in Burma. | |||

==Burma== | ==Burma== | ||

see [[Burma Road and Ledo Road]] | see [[Burma Road and Ledo Road]] | ||

| Line 17: | Line 20: | ||

By the start of 1944, as the airlift's capability soared, American strategists moved beyond a concern for Chinese national will and used the airlift as the primary means of supplying American forces in China in preparation for the final assault on Japan. Strictly from the standpoint of war materiel, the airlift set the preconditions that had to be met to make possible all other allied military action, and dictated the level of effort the Americans could bring to bear against the Japanese, being the sole route to China until early 944, when the Ledo Road opened. Other routes were discussed and attempted, but in the end the only way for supplies to get into China was over the Himalayas. In addition to being an enabler, the airlift was also a driver of CBI strategy, as it was an expression of the broader airpower orientation of the theater. Difficult terrain, extreme weather, and primitive roads all combined to make the CBI a theater best traversed by air. It was in the CBI, and only in the CBI, that allied troops were most commonly inserted, supplied, and extracted by air.<ref> See John D. Plating, "Keeping China in the War: The Trans-Himalayan `Hump' Airlift and Sino-US Strategy in World War II." PhD dissertation Ohio State U. 2007. </ref> | By the start of 1944, as the airlift's capability soared, American strategists moved beyond a concern for Chinese national will and used the airlift as the primary means of supplying American forces in China in preparation for the final assault on Japan. Strictly from the standpoint of war materiel, the airlift set the preconditions that had to be met to make possible all other allied military action, and dictated the level of effort the Americans could bring to bear against the Japanese, being the sole route to China until early 944, when the Ledo Road opened. Other routes were discussed and attempted, but in the end the only way for supplies to get into China was over the Himalayas. In addition to being an enabler, the airlift was also a driver of CBI strategy, as it was an expression of the broader airpower orientation of the theater. Difficult terrain, extreme weather, and primitive roads all combined to make the CBI a theater best traversed by air. It was in the CBI, and only in the CBI, that allied troops were most commonly inserted, supplied, and extracted by air.<ref> See John D. Plating, "Keeping China in the War: The Trans-Himalayan `Hump' Airlift and Sino-US Strategy in World War II." PhD dissertation Ohio State U. 2007. </ref> | ||

==Historiography and memory== | |||

The CBI theater has been largely ignored by historians, apart from the outstanding official histories by Romanus, Charles F. and Riley Sunderland (1953-58), and Barbara Tuchman's Pulitzer-Price biographyof Stilwell. Public memory keeps alive with stories of the horrors of Japanese POW camps, and the building of the railroad, as marked by the Oscar-winning "Bridge on the River Kwai" (1957). The Japanese have erased the war years from their textbooks, angering their victims. War memories of massacres and hardship remain all too vivid in China.<ref>Rana Mitter, "Remembering the Forgotten War." ''History Today'' 2005 55(8): 17-19. Issn: 0018-2753 Fulltext: [[Ebsco]] </ref> | |||

==Bibliography== | ==Bibliography== | ||

* Bidwell Shelford. ''The Chindit War: Stilwell, Wingate, and the Campaign in Burma, 1944.'' (1979) | * Bidwell Shelford. ''The Chindit War: Stilwell, Wingate, and the Campaign in Burma, 1944.'' (1979) | ||

Revision as of 11:31, 23 June 2008

The China-Burma-India (CBI) theater was created by the U.S., Britain and China and operated 1941 to 1945 to fight Japan on the mainland of Asia.

Strategy

see Joseph Warren Stilwell The stunning speed of the Japanese conquests in 1941-42 stunned China. In eight weeks the Japanese sank the American battle fleet at Pearl Harbor, knocked out American air power in the Philippines, captured Hong Kong, sank the British and Dutch fleets, captured Malaya and the impregnable fortress of Singapore, and finally captured Rangoon, cutting off the Burma Road lifeline to China. The British, primarily concerned with India, looked to Burma as the main theater of action against Japan and wanted Chinese troops to fight there. The United States conjured up visions of millions of Chinese soldiers who would hold the Japanese then throw them back, while providing close-in airbases for a systematic firebombing of Japanese cities. Chiang realized it was all fantasy. On the other hand there were vast sums of American dollars available if he collaborated. He did so and managed to feed his starving soldiers, but they were so poorly equipped and led that offensive operations against the Japanese in China were impossible. However, Chiang did release two Chinese armies for action in Burma.

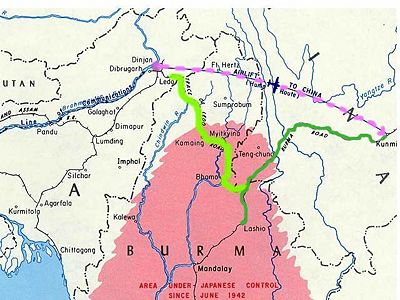

Burma

China

see Chiang Kai-shek

Air War

Cheannault

Flying the Hump

The trans-Himalayan airlift, the "Hump," was the first sustained and most ambitious combat airlift operation in modern history. Cobbled together with only a handful of airplanes and aircrews in early 1942, the operation grew to become the ultimate expression of American commitment to keeping China in the war and using its airfields to attack Japan. In all it delivered 740,000 tons of cargo, flying in some of the world's worst weather system and over its most rugged terrain, all the while under the threat of enemy attack.

The Hump airlift was initially started to serve as a display of American support for its Chinese ally who had been at war with Japan since 1937. Motivations behind the airlift's execution changed during the war. Once the US entered the war, the Hump was seen as an extension of its (pre-December 1941) Lend-Lease aid to China, aid that had previously been delivered over the Burma Road, but that route was cut off by the Japanese in the spring of 1942. The airlift became the only means to supply China and "keep China in the war." To the US, China's national will was tottering as a result of its brutal war with Japan since 1937, and the influx of US material over the Himalayas was the best way to prevent Chinese capitulation.

By late 1943 the airlift became the centerpiece of US strategy focused on the destruction of Japan. The Hump would enable China-based B-29 bombers to begin striking the Japanese home islands, which supposedly were made of such fragile paper-and-wood construction they would easily burn down. Second, the airlift delivered a stockpile of supplies at in preparation for the planned Army invasion of Japan. Hump tonnage skyrocketed in 1944-45 because of the growth of its infrastructure that included a robust air traffic control system, innovative maintenance procedures, dozens of navigation aid-equipped airfields, hundreds of airplanes, and thousands of pilots. All of this combined to dwarf tonnage delivered to China on land routes, ushering in a paradigm shift in the history of wartime logistics that saw airlift become the most efficient and durable means of supply.

By the start of 1944, as the airlift's capability soared, American strategists moved beyond a concern for Chinese national will and used the airlift as the primary means of supplying American forces in China in preparation for the final assault on Japan. Strictly from the standpoint of war materiel, the airlift set the preconditions that had to be met to make possible all other allied military action, and dictated the level of effort the Americans could bring to bear against the Japanese, being the sole route to China until early 944, when the Ledo Road opened. Other routes were discussed and attempted, but in the end the only way for supplies to get into China was over the Himalayas. In addition to being an enabler, the airlift was also a driver of CBI strategy, as it was an expression of the broader airpower orientation of the theater. Difficult terrain, extreme weather, and primitive roads all combined to make the CBI a theater best traversed by air. It was in the CBI, and only in the CBI, that allied troops were most commonly inserted, supplied, and extracted by air.[1]

Historiography and memory

The CBI theater has been largely ignored by historians, apart from the outstanding official histories by Romanus, Charles F. and Riley Sunderland (1953-58), and Barbara Tuchman's Pulitzer-Price biographyof Stilwell. Public memory keeps alive with stories of the horrors of Japanese POW camps, and the building of the railroad, as marked by the Oscar-winning "Bridge on the River Kwai" (1957). The Japanese have erased the war years from their textbooks, angering their victims. War memories of massacres and hardship remain all too vivid in China.[2]

Bibliography

- Bidwell Shelford. The Chindit War: Stilwell, Wingate, and the Campaign in Burma, 1944. (1979)

- Byrd Martha. Chennault: Giving Wings to the Tiger. (1987).

- Callahan Raymond. Burma, 1942-1945. (1978).

- Callahan Raymond. The Worst Disaster: The Fall of Singapore. (1977).

- Ch'i, Hsi-sheng. Nationalist China at War: Military Defeats and Political Collapse, 1937–1945 (1982)

- Craven Wesley Frank, and James Lea Cate, eds. The Army Air Forces in World War II. 7 vols. 1948- 1958.

- vole 4: The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan: August 1942 to July 1944 table of contents

- vol 5: The Pacific--Matterhorn to Nagaski, June 1944-August 1945 (1953) table of contents and some text

- Dod Karl C. The Corps of Engineers: The War against Japan. (1966),

- Dreyer, Edward L. China at War, 1901-1949. (1995). 422 pp.

- Eastman Lloyd et al. The Nationalist Era in China, 1927-1949 (1991) excerpt and text search

- Falk Stanley L. Seventy Days to Singapore: The Malayan Campaign, 1941-1942. (1975).

- Fenby, Jonathan. Chiang Kai Shek: China's Generalissimo and the Nation He Lost (2004), 592pp excerpt and text search

- Hogan. David W. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II: India Burma online edition

- Hough Richard. Mountbatten: Hero of Our Time. (1980).

- Hsi-sheng, Ch'i. Nationalist China at War: Military Defeats and Political Collapse, 1937–1945 (1982)

- Hsiung, James C. and Steven I. Levine, eds. China's Bitter Victory: The War with Japan, 1937-1945 (1992), essays by scholars; online from Questia; also excerpt and text search

- Kirby S. Woodburn. Singapore: The Chain of Disaster. (1971).

- Kirby S. Woodburn. The War against Japan. ( Vols. 1-5. 1957- 1969), official British history; highly detailed.

- La Robert S. Forte, and Ronald E. Marcello. Building the Death Railway: The Ordeal of American POWs in Burma, 1942-1945. (1993).

- Lee, Lloyd, ed. World War II in Asia and the Pacific and the War's aftermath, with General Themes: A Handbook of Literature and Research. (1998) online edition

- Lewin Ronald. The Chief: Field Marshal Lord Wavell, Commander-in-Chief and Viceroy, 1939-1947. (1980).

- Lewin Ronald. Slim: The Standardbearer. (1976).

- Liang, Chin-Tun. Gen. Stilwell in China, 1942-1944 (1972), a pro-Chiang view

- Morley James, ed. The Fateful Choice: Japan's Advance into Southeast Asia, 1939-1941. (1980).

- Plating, John D. "Keeping China in the War: The Trans-Himalayan `Hump' Airlift and Sino-US Strategy in World War II." PhD dissertation Ohio State U. 2007. 397 pp. DAI 2007 68(4): 1627-A. DA3262108 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses

- Prasad B., ed. Official History of the Indian Armed Forces in the Second World War (1939-1945). (Delhi: Orient Longmans, 1954- ).

- Romanus, Charles F. and Riley Sunderland. Stilwell's Mission to China (1953), official U.S. Army history online edition; Stilwell's Command Problems (1956) online edition; Time Runs Out in CBI (1958) online edition. Official U.S. Army history

- Rooney David. Burma Victory: Imphal, Kohima and the Chindit Issue. (1992).

- Schaller Michael. The U.S. Crusade in China, 1938-1945. (1979). online edition

- Thorne Bliss K. The Hump: The Great Military Airlift of World War II. (1965).

- Tuchman, Barbara. Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-45, (1972), 624pp; Pulitzer prize (The British edition is titled Against the Wind: Stilwell and the American Experience in China 1911-45,) excerpt and text search

- Ziegler Philip. Mountbatten: The Official Biography (1985).

Primary Sources

- Chiang Kai-Shek. The Collected Wartime Messages of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, 1937-1945, (1946) online edition

- Stilwell, Joseph Warren. The Stilwell papers edited by Theodore H. White, (1958).

- Stone, James H. ed. Crisis Fleeting: Original Reports on Military Medicine in India and Burma

in the Second World War, (1969) online edition