Northern Ireland: Difference between revisions

imported>Richard Jensen (add) |

imported>Donal O'Hara No edit summary |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

Northern Ireland consists of 6 of the counties of Ulster: Antrim, Armagh, Derry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone; with Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan being part of the Republic of Ireland. The region is bordered with the [[North Sea]] on its North coast, the Irish sea on its East coast and the Republic of Ireland to the South and West. | |||

==Economy== | ==Economy== | ||

==Government== | ==Government== | ||

Revision as of 20:00, 3 July 2008

Northern Ireland is a region of the British Isles, situated on the island of Ireland, to the north and east of the Republic of Ireland. It is separated from Scotland by the North Channel. Northern Ireland was established by the Government of Ireland Act, 1920, and it is a constituent part of the United Kingdom. It has been a tumultuous spot of perennial strife between the supporters of its union with the U.K. (Ulster Unionism), and supporters of its unification with the Republic of Ireland (Irish Republicanism).

Geography

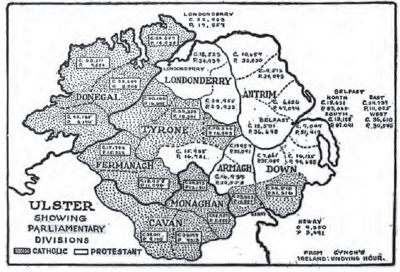

Northern Ireland consists of 6 of the counties of Ulster: Antrim, Armagh, Derry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone; with Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan being part of the Republic of Ireland. The region is bordered with the North Sea on its North coast, the Irish sea on its East coast and the Republic of Ireland to the South and West.

Economy

Government

Culture

History

See:

Historiography

Regan (2007) asks to what extent has the recent war in Northern Ireland influenced Irish historiography? Examining the nomenclature, periodization, and the use of democracy and state legitimization as interpretative tools in the historicization of the Irish Civil War (1922–3), the influence of a southern nationalist ideology is apparent. A dominating southern nationalist interest represented the revolutionary political elite's realpolitik after 1920, though its pan-nationalist rhetoric obscured this. Ignoring southern nationalism as a cogent influence has led to the misrepresentation of nationalism as ethnically homogeneous in twentieth-century Ireland. Once this is identified, historiographical and methodological problems are illuminated, which may be demonstrated in historians' work on the revolutionary period (c. 1912–23). Following the northern crisis's emergence in the late 1960s, the Republic's Irish governments required a revised public history that could reconcile the state's violent and revolutionary origins with its counterinsurgency against militarist-republicanism. At the same time many historians adopted constitutional, later democratic, state formation narratives for the south at the expense of historical precision. This facilitated a broader state-centred and statist historiography, mirroring the Republic's desire to re-orientate its nationalism away from irredentism, toward the conscious accommodation of partition. Reconciliation of southern nationalist identities with its state represents a singular political achievement, as well as a concomitant historiographical problem.[1]