Phishing

Phishing is a term originating with the computer industry but now in general use that describes a type of fraud in which the victim is induced to divulge personal confidential information, such as an account username and password, usually for an online banking or financial service. The term, with its unusual spelling, derives from the associated but older term phone phreaking or just phreaking, which refers to hacking into telephone systems.

A typical phishing attempt uses social engineering techniques to prey on the fears of uninformed users of financial and other online systems. By tricking such users into divulging their account credentials, the fraudsters can then access the compromised accounts and transfer the funds therein to a holding account, which will then be quickly emptied.

Method

The fraudsters will first set up a page or pages on a website, designed to mimic that of their target financial institution. Quite often, the pages will be uploaded to an innocent website that has been hacked; the legitimate owner of the website will be unaware that it is being used in this fashion. Then, using a botnet or other similar means, the perpetrators will send a carefully constructed email to a massive number of recipients. The email will use copied logos, embedded in the mail, to give the appearance that it is coming from the financial institution in question. It will generally employ email spoofing methods to disguise the sender's address and to make it appear as if it is coming from the financial institution in question.

While many of these mails will be caught by spam filters and other protections, some will make it through to the mailboxes of people who have accounts with the target financial institution. A person clicking on one of the links contained in the email will be brought not to the financial institution's website, but to the fake one that has previously been set up. If the mail recipient does not notice that they are at a fake site and enters their credentials, the fake site will record these details. The fraudsters can then access the account themselves and empty it of funds.

The image to the right shows one such typical email. The example represents a relatively poor attempt at a phishing mail. Notice the lack of an entry in the "To:" field of the email; lack of a personalised greeting; and the very unclear (and ungrammatical) reason stating why the person's details are required: "<website> cam shows We must properly verify your account again." The faked logo is used only once. Phishing mails can often be far more sophisticated.

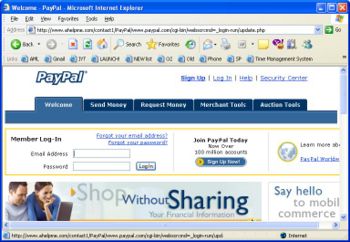

Clicking on a link in the above email brings the user to the website pictured left. Again, this is not a very sophisticated example, but much more believable sites are used. In this screenshot, we can see that although the website purports to be Paypal, the browser address bar is that of a completely different site. Similarly, hovering the cursor over a hyperlink shows that by clicking on a link, the user will be brought to a page not hosted by Paypal.

Faked sites have been made to look more convincing by several methods. Two common examples include using scripts hosted on the website, which serve to disguise the website's address as displayed in the address bar and to disguise the true destination of hyperlinks as displayed in the status bar; and to construct a website address using non-standard characters, which nonetheless appear at a casual glance to be that of the expected website.

Cost

As far back as 2004, Gartner Research estimated that the cost of phishing frauds to banks and credit card companies was US$1.2 billion, in the United States of America alone.[1]

Effectiveness

Unfortunately for financial institutions and victims of phishing attempts, this method of fraud has proven to be highly successful. The main cause is a lack of knowledge and education about online safety on the part of end users. While the computer is ubiquitous in most developed countries and people have taken to the convenience of online services, few take the trouble to keep abreast of the latest security threats.

While computer users may therefore be vaguely aware of threats to the security of their online accounts, they may not be aware of the specifics involved - despite efforts by financial institutions to educate them. Therefore when they receive an email purporting to come from their bank, possibly warning (as many phishing mails do) that their account may have been compromised and that they need to verify their credentials, they follow the instructions without the necessary knowledge to detect a fraudulent email or website.

Financial institutions themselves may have partly contributed to this problem - many use website addresses for their online banking functions that are substantially different from the bank's normal internet domain. Similarly, many regularly email their customers from addresses different to the normal domain.

Scope

While the current main target of phishing attempts is online bank accounts, the first attempts were against Internet Service Providers such as AOL. In theory, though, any online service may be targeted, especially where there is a possibility of financial gain. An example outside the banking sphere is the MMORPG World of Warcraft. Following the announcement of the both game's second and third expansions, phishing attempts were launched targeting playes of the game - the mails in question offering players access to the beta test. Links in the emails led to faked World of Warcraft websites, which sought the visitor's game username and password. Players who fell for this scam would soon find that their account had been compromised, with all in-game items and gold missing (in-game "gold" being sold in the real world is a lucrative business).

Spear phishing

Recently the term spear phishing has come into use for carefully targeted phishing attacks. [1] Where many phishing attacks spread a fairly wide net — often spamming thousands of people in hopes of catching a few — spear fishing is aimed at specific targets. For example, to get information on a military project such as new jet fighter, one might target engineers or executives at the contracting company.

Often considerable work is done to craft attacks for specific targets. For example, in the Aurora attacks against Google and others [2], the attackers appear to have used social networking sites such as Facebook to research the targets, so that they could forge email that appeared to be from a trusted contact. They also built different variants of their malware package for different target organisations, depending which anti-virus packages were in use. In another case, Canadian government computers were targetted. [3]

This sort of attack raises the stakes; it is not just a general threat to computer security, but a very specific threat to high-value secrets. The effort involved generally makes it too expensive for a simple attack aimed at credit card fraud. However, it may be just the thing for industrial or international espionage where both the potential payoffs and the available resources tend to be much larger.

Pharming

Another variant is pharming: the attacker subverts DNS so that it gives false information which sends you to an attack site. One attack subverted several hundred thousand SOHO routers [4]; it just changed their DNS settings so they would get their information from an attacker-controlled server.

Watering hole attack

A related problem is the watering hole attack, named after the hunter's technique of waiting near water for prey to arrive. One plants malware on some server used by a target community and hopes to infect as many victims as possible as they pass by. For example, in February 2012, a group of attacks on Apple, Facebook and Twitter were all traced to a watering hole attack on a forum popular with developers of Apple IOS applications [5]. In 2014, an attack of this type was discovered that was apparently aimed at stealing American military secrets [6]; it used a site for veterans.

Once an attacker has a few infected machines, they can be exploited in various ways, perhaps most notably stealing those users' credentials for direct attacks on other systems or in collecting information such as people's contact lists which can be used either for their intelligence value (see traffic analysis) or to help set up additional attacks such as spear phishing.

This is a difficult one for the defenders. In the example, it is almost impossible for Apple, Facebook or Twitter to prevent the original infection, since that occurs outside their control; by the time those sites see the problem the user's machine is already infected. They can work to limit the damage this does to their systems, but it is hard to do that without restricting legitimate services to your users.

On the other hand, the attack has almost no consequences on the forum systems, so the admins there may not notice it, or may not consider it a high-priority problem if they do. After all, they are just running a forum and all their data is public anyway; what is there to protect?

Protection

There are two main methods of preventing successful phishing attacks. The first is user education. This involves educating end-users of online financial websites about the reality and methods of identity theft, including phishing, and advising them of the methods to avoid falling for such frauds. As outlined above, this has proven to be a difficult task.

The second method is to use software that will intervene to directly warn the user when a possible phishing attempt is detected, or otherwise make the fraudsters' emails and websites more obvious as fakes. Both Microsoft's Outlook email program and Google's web-based Gmail, to give but two examples, attempt to deter users from accessing phishing emails. Outlook does this by requiring user intervention before displaying graphics embedded in an email - and presumably the end user will wonder why they need to authorise a download from their financial institution, which would likely already have been authorised. Gmail places a warning directly onto each email it perceives as a phishing attempt.

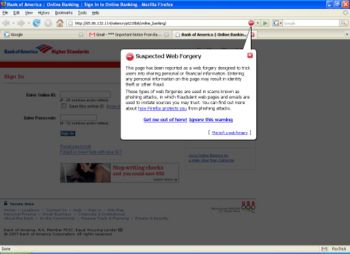

Similarly, some web browsers will alert users to potential phishing websites. Pictured right, is the very obvious popup deployed by the Firefox web browser (version 2.0.0.6) to alert the user that a potentially fraudulent website has been visited. The web page is greyed out, and the user is warned, given the option of getting more information, or continuing - but can't interact with the web page until they have chosen one or the other. Internet Explorer (version 7 and above) includes phishing protection, and a button on the status bar allows the user to check whether the page they have visited is a reported phishing website.

Another line of defense using software is the newest generation of security suite, which in addition to the usual anti-virus and firewall software, may now contain anti-malware features including detection of phishing attempts.

References

- ↑ Internetnews.com: Cost to business of phishing: Available: http://www.internetnews.com/ec-news/article.php/3350891 Retrieved: 5th September 2007.